Growing up in Miami among Cuban exiles who fled Fidel Castro’s revolution, Sen. Marco Rubio developed a deep hatred of communism. Now as President-elect Donald Trump’s choice for America’s top diplomat, he’s set to bring that same ideological ammunition to reshaping U.S. policy in Latin America.

Read More: How Asia and Africa Are Bracing for Trump’s Second Term

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]As the first Latino secretary of state, Rubio is expected to devote considerable attention to what has long been disparagingly referred to as Washington’s backyard.

The top Republican on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and a longtime member of the Foreign Relations Committee, he’s leveraged his knowledge and unmatched personal relationships to drive U.S. policy in the region for years.

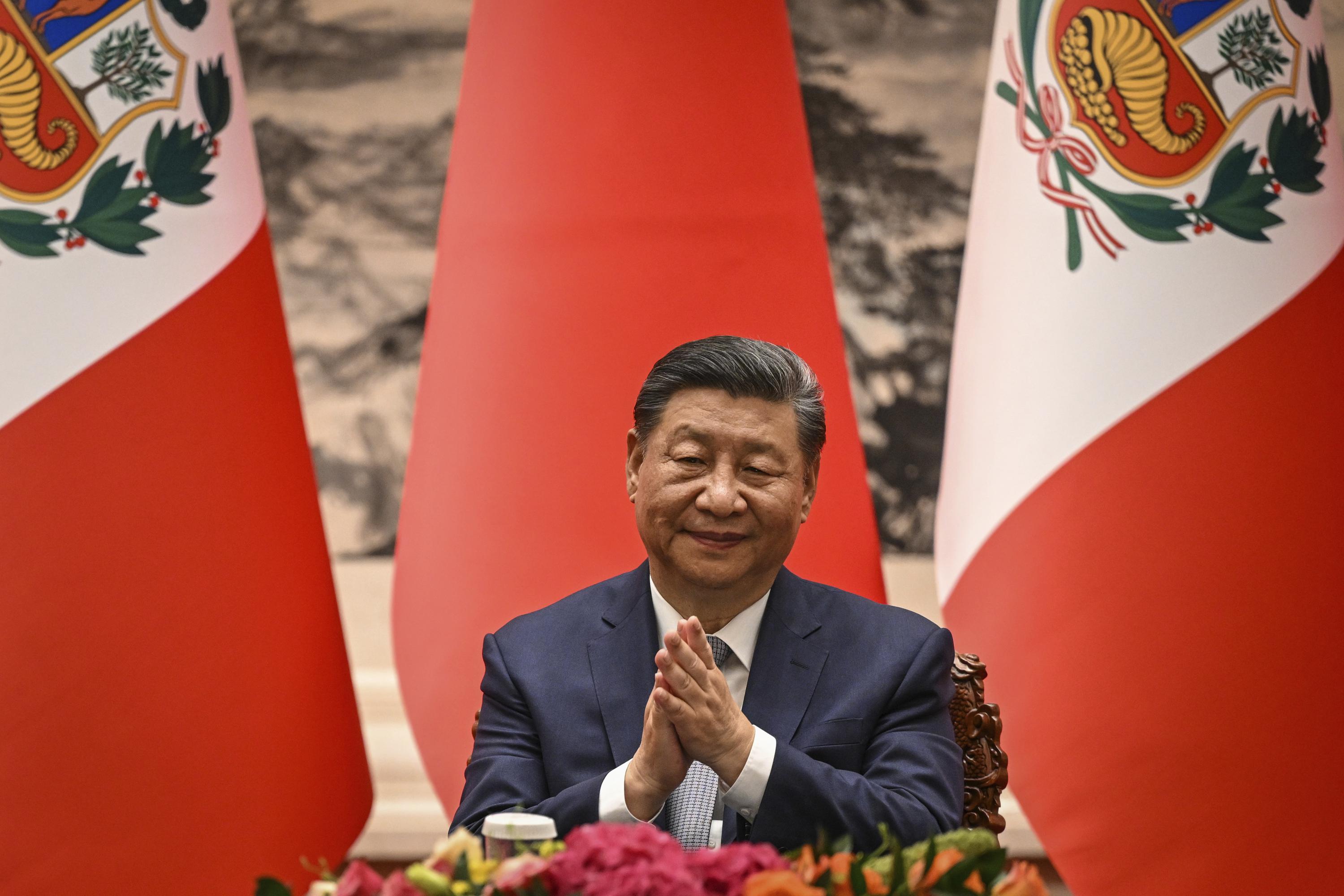

For decades since the end of the Cold War, Latin America has faded from the U.S. foreign policy agenda even as U.S. adversaries like Russia, Iran and especially China have made deep inroads. If confirmed, the Florida Republican is likely to end the neglect.

But Rubio’s reputation as a national security hawk, embrace of Trump’s plan for mass deportation of migrants and knack for polarizing rhetoric is likely to alienate even some U.S. allies in the region unwilling to fall in line with the incoming President’s America First foreign policy.

“Typically, Latin America policy is left to junior officers,” said Christopher Sabatini, a research fellow at Chatham House in London. “But Rubio’s reflexes are firmly focused on the region. He’ll be paying attention, and governments are going to have to be more cooperative in their larger relationship with the U.S. if they want to draw close.”

Rubio, through a Senate spokeswoman, declined to comment about his foreign policy goals.

But his views on Latin America are well known and contrast sharply with the Biden administration’s preference for multilateral diplomacy and dialogue with U.S. critics.

Taking cues from his boss, Rubio’s main focus in the region is likely to be Mexico, on trade, drug trafficking and migration. Once a sponsor of bipartisan reforms allowing undocumented migrants a path to citizenship, Rubio transformed himself during Trump’s first administration into a loyal supporter of his calls for increased border security and mass deportation.

Rubio has said little about Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, who took office last month. But he was a fierce critic of her predecessor, Andres Manuel López Obrador, who in 2022 defiantly skipped the U.S.-organized Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles for a gathering of leftist leaders in Cuba.

Rubio accused López Obrador of capitulating to drug cartels and serving as an “apologist for tyranny” in Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. The Mexican President responded by calling Rubio a “racist.”

Despite the snub, the Mexican President was welcomed by President Joe Biden to the White House three weeks later as a “friend” and “partner.”

“That won’t happen under Rubio,” said Sabatini. “He keeps close tabs on who is following his policy preferences.”

Rubio, 53, has long had Trump’s ear on Latin America—and hasn’t hesitated to use that access to promote his hard-line agenda. He’s been one of the most outspoken critics of Russian and Chinese economic, political and military outreach in the region, and is expected to punish countries who cozy up to America’s geopolitical rivals, or those who fail to support Israel.

When Trump canceled what would have been his first presidential visit to Latin America in 2018, Rubio was there to fill the void, sitting for meetings and photo ops at the Summit of the Americas in Peru with regional leaders from Argentina, Haiti and elsewhere.

“There’s nobody in the U.S. Senate who comes close to having his affinity and depth of knowledge on Latin America,” said Carlos Trujillo, Rubio’s close friend and former U.S. ambassador to the Organization of American States. “Not only does he have personal relationships with dozens of officials, some of them for decades, but he has vetted almost every U.S. ambassador deployed to the region. It’s a significant advantage.”

Among those eager to work with Rubio is Argentine President Javier Milei, whose combative style, attacks on institutions and transformation from TV personality to far-right leader have drawn comparisons with Trump.

Another ally is El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, whose crackdown on gang violence that once drove millions of Salvadoran migrants to the U.S. has drawn praise from Rubio.

Rubio hasn’t hesitated to use his power to bully leftist leaders he sees as harming U.S. national security interests. Even democratically elected moderates have been targets. Earlier this year, he slammed Chilean President Gabriel Boric, a critic of Israel’s actions in Gaza, for allegedly providing safe haven for Hezbollah financiers, calling him “one of the leading anti-Israel voices in Latin America.”

In 2023, he called Colombian President Gustavo Petro, a former member of the M-19 guerrilla group, a “dangerous” choice to lead a country that has been the longtime U.S. partner in the war on drugs.

But it is on Venezuela that Rubio has left his biggest mark.

Within weeks of Trump taking office in January 2017, Rubio brought the wife of prominent Venezuelan dissident Leopoldo Lopez to the White House. The Oval Office visit, marked by a photo of a grinning Trump and Rubio flanking the then jailed activist’s wife, immediately thrust Venezuela to the top of the U.S. foreign policy agenda, in a break from previous U.S. administrations efforts to keep a distance from the nation’s troubles.

Over the next two years, Trump slapped crushing oil sanctions on Venezuela, charged numerous officials with corruption and began talking of a “military option” to remove President Nicolás Maduro. In 2019, at the height of Rubio’s influence, the U.S. recognized National Assembly President Juan Guaidó as the country’s legitimate leader.

But the combative stance—popular among exiles in South Florida—came to haunt Trump, who later recognized he had overestimated the opposition. By strengthening Maduro’s hand, it also paved the way for deeper Russian, Chinese and Iranian interests in the country, all the while aggravating a humanitarian crisis that led millions to uproot, with many migrating to the U.S.

Michael Shifter, the former president of the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, believes Trump may prove more forgiving of Maduro this time, even with Rubio heading the State Department, and continue the path of engagement and sanctions relief pursued by the Biden administration.

“Trump may begin to treat Maduro as he typically treats other strongmen around the world, and cater a bit less to the Cuban-American exile community in Florida,” Shifter said.

Trujillo said Rubio’s reputation for candor will serve him well negotiating with America’s friends and foes alike, even if he has to temper his sometimes-heated rhetoric.

“He’s going to be playing a different role now, but he’s an exceptional negotiator and I have no doubt he will rise to the occasion,” Trujillo said.

With Trump’s selection of another vocal Maduro critic, Rep. Michael Waltz of Florida, as his national security adviser, Trujillo said the Venezuelan leader and his authoritarian allies in Cuba and Nicaragua should be worried.

So far, officials in Venezuela and Cuba, who routinely criticize the U.S. on social media, haven’t commented on Rubio’s nomination and have remained largely muted on Trump’s victory.

“There is an opportunity to negotiate but it will have to be in good faith,” Trujillo said. “If they don’t, there will be consequences.”

—Goodman reported from Miami. Mark Stevenson and Maria Verza in Mexico City and Isabel DeBre in Buenos Aires contributed to this report.